Justice like a thunderbolt

June 26, 2015 marked an unforgettable day in the Obama Presidency. The Supreme Court ruled on marriage equality, President Obama paid tribute to Reverend Pinckney and his eight parishioners in Charleston, and the White House shone with pride for all to see.

To mark the anniversary of that fateful day, we created a retrospective video and collected reflections of many who experienced it firsthand.

June 26, 2015, also marked the end of a unique ten-day stretch in American history. After the murder of nine parishioners at Mother Emanuel AME Church by a white supremacist, organizers held protests in South Carolina that led to the removal of the Confederate flag from the State house grounds. The Supreme Court upheld a critical piece of the Affordable Care Act in King v. Burwell , guaranteeing that millions of Americans would not lose their health insurance. And on the morning of June 26, millions of Americans were waiting to hear how those same justices would rule on the question of whether same-sex couples had the right to marry, in Obergefell v. Hodges.

As so many who lived through that day will tell you, that morning’s decision was decades in the making. It was a moment made possible by the work of activists who demanded justice, government leaders who took action, and millions of ordinary Americans who dared to live openly and challenge their government to honor their commitment.

The path to progress rarely runs in a straight line. Broader cultural support for gay rights was routinely met with legal resistance. The path to racial progress has long been punctuated by horrific acts of white supremacist violence. And through the long arc of history, it can be difficult to see how an individual act—a cry of grief, a protest, a phone call to a representative, a ballot cast—can lead to justice.

But once in a while, that work adds up to days like June 26, 2015, where justice arrives, “like a thunderbolt.”

Love Wins

Jeff Tiller, White House Director of Specialty Media: I woke up sick to my stomach at 5am. I thought, I need to get to the White House early—I think this is the day the Supreme Court decision might come down.

Cody Keenan, White House Director of Speechwriting: That Friday was one of nervous energy for most of the staff. None of us knew which way the Supreme Court case was going to go. We knew something was going to happen at 10am, but we didn’t know what.

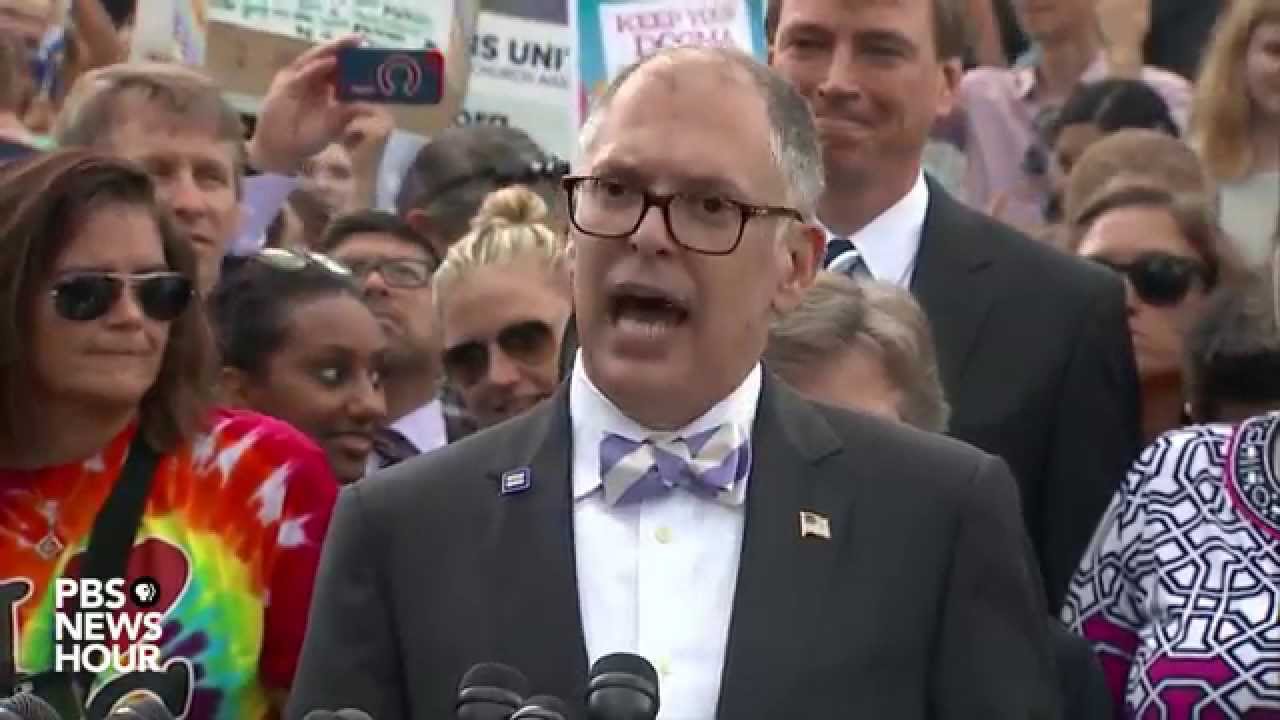

Jim Obergefell, Plaintiff, Obergefell v. Hodges : Obergefell v. Hodges came about because my late husband, John, and I had been together for almost 21 years, and we lived in Ohio, a state where we could not legally marry.

Then, on June 26, 2013, the Supreme Court ruled in United States v. Windsor , that the Defense of Marriage Act, was unconstitutional (Opens in a new tab) ; and in that moment, when we heard that news, I spontaneously proposed to John.

But then we had to figure out, “Well, how do we get married?” Here we are in Cincinnati, Ohio, where we cannot go six blocks to our county courthouse for a marriage license, and to complicate matters, John was nearing the end of his life due to ALS, and he was completely bedridden.

So, the thought of putting him in an ambulance to take a journey to another state to get married was problematic. I certainly couldn’t take him to the airport to fly commercially; that just wasn’t doable. But we desperately wanted to get married. We settled on Maryland, because it was the one state that did not require both parties to appear in person to apply for a marriage license, and that really helped with my goal to make sure John’s pain was kept to a minimum. I could go in advance, get the marriage license; then, the two of us could go purely to get married, to say “I do.” But how do we get there?

That ended up being a chartered medical jet. Through the generosity and support of our family and friends, they raised the entire cost of that medical jet, which was almost $14,000. We flew to Baltimore/Washington International Airport, along with John’s aunt, Paulette, and parked on the tarmac. We never left that airplane. In that airplane, we got to say those words we had always wanted to say, “I do.” We got to commit ourselves legally and publicly to each other as a married couple.

We flew back to Cincinnati, and we thought that was the end of it. Well, fate had a different idea in mind, and because of a story about us in our local newspaper, friends connected us with a civil rights attorney in Cincinnati, Al Gerhardstein. Al pulled out the blank Ohio death certificate, and said, “Now, guys, do you understand that when John dies, his last record as a person, his last official record as a citizen, will be wrong? Ohio will say he’s unmarried, and Jim, your name won’t be there as his surviving spouse.”

It broke our hearts. But I think even more importantly, it made us angry, and when Al asked if we wanted to do something about it, we discussed it and said, “Yes, we do.” So, eleven days after we got married, I was in federal district court for the first hearing in our case. We sued the State of Ohio and the City of Cincinnati to demand that when John died, his death certificate would recognize our lawful out-of-state marriage.

This moment, this conversation with Al Gerhardstein in our home, was when we understood, this is how we’re being harmed. This is how we’re being denigrated and ignored… that was the moment when my activism was born, but it’s also the moment that I realized this is a fight, this is a lawsuit that could have much greater impact outside of just our marriage.

It became a consolidated case with more than 30 other plaintiffs from three states, including all of those other plaintiffs: another widower; a funeral director; same-sex couples who wanted to get married; same-sex couples who had been married, but wanted their marriage recognized by their home state; and children. So, we very quickly realized that there’s a lot more being impacted by our case. It isn’t just John’s and my demand to matter—our request to be respected. We were making that same demand for countless people across our nation.

Sarada Peri, White House Senior Speechwriter: I was told by our Counsel’s office there were several ways this ruling could go: we could lose outright—the Court could decide same-sex couples had no right to marry; we could win outright—the Court could rule that all same-sex couples had the right to marry; the court could rule narrowly on this one case, but not settle the question of whether marriage equality is the law of the land and leave it to the states to decide; or we could lose on the narrow question of this case and the Court would take no position on the broader issue at all.

What that means for a speechwriter is that you have to write four different speeches. So I wrote a “we lost” version, and then crafted the legal explanation—in plain English—for the other two scenarios, in case the court ruled narrowly.

I’m superstitious, so I didn’t write a victory speech. I wrote a few sentences to put a win in the context of the broader fight and had details like Jim Obergefell’s relationship that I was ready to go with. But I didn’t actually write, “We won,” because I just didn’t think it was going to happen. I didn’t want to jinx it.

Valerie Jarrett, Senior Advisor to President Obama: We were in the chief of staff’s office, having our normal morning meeting when my assistant rushed in at a few minutes after 10am with a note saying that the marriage equality decision had come down.

Sarada Peri: Suddenly I hear yelping in the hallway, and Megan Rooney, one of the speechwriters, emails all of us: “TOTAL VICTORY!”

Jeff Tiller: All you could hear was colleagues celebrating, screaming in the halls. There was this… euphoria . Everyone was hugging and high-fiving.

Jim Obergefell: I was in that courtroom that day as Justice Kennedy began to read his decision. I realized, “Yes, he’s saying we matter, we exist.” I broke into tears, along with so many people in that courtroom, spectators, and attorneys alike.

Aditi Hardikar, White House Associate Director of Public Engagement: It was an incredible, incredible moment. It felt like our lives were validated. It felt like all of the things that activists for decades before us had been working towards paid off in such a huge way. Not that marriage equality was the end all, be all by any means—there is still so much work we have to do in our community—but it was such a pivotal front and center moment that affirmed the lives of our community.

Jim Obergefell: My first thought was, “John, I wish you were here. I wish you could experience this to know that we matter, to know that your death certificate will never change, to know that you will always be my husband.”

Missing John and wishing he were there was closely followed by the realization that, for the first time in my life as an adult gay man, and an out gay man, I felt like I was equal. I felt like an equal American.

Cody Keenan: What I remember in retrospect is the scenes of joy on TV. In front of the court you saw people who were euphoric because their lives had just been deemed equal to everybody else’s. And a lot of people in the administration and across the country all felt that same validation and euphoria. It was impossible not to get swept up in that.

Jim Obergefell: After the decision, we made our way through the crowd in front of the Supreme Court. The air was electric. The feeling of joy and celebration was overwhelming, people were crying and giving us high-fives, and cheering and singing. It was this beautiful moment of feeling like I belonged.

I had an interview with a CNN crew, and then someone said, “Jim, you have a phone call,” and they handed me a phone, on speaker.

Jim Obergefell: Looking back at that conversation with President Obama, he said that my leadership made a difference. That isn’t something I’ve ever been comfortable with—being called a leader—because I don’t necessarily feel like I’m a leader. I feel like I simply did what the right thing was to do in regards to this case, in regards to my husband, in regards to living up to my promises to love, honor, and protect.

It is very strange to realize I am the face and name of a landmark Supreme Court decision. It seems weird to know that I was part of something so major. The funny thing is, John and I were never activists. We were what we call, “checkbook activists.” We would support organizations and causes that we believed in, but we were never those people who joined protests or who did other things in the realm of activism. That wasn’t who we were.

Sarada Peri: What struck me about Jim and the plaintiffs is that they did not go into this as cultural figures—they weren’t famous, they weren’t trying to be known. They were just trying to live their lives. And there are all these millions of people who you don’t even know, who were part of making this change in their own quiet ways. Every day, ordinary heroes who put themselves out there—who put their livelihoods and reputations on the line to live their lives and be who they were, and help other people get to a place where they saw them as human.

Jim Obergefell: I think about all of the people who came before me, the people who helped create a world where we could do that. I think about all of those other people, who risked everything to live an authentic life. They risked their jobs, they risked their families, they risked their lives to say, “I am gay. I am a lesbian.” They risked everything to live openly and authentically, and if it weren’t for them, I would have never found myself in that spot.

Aditi Hardikar: After the decision came down, there were all these things that had to be put into motion. We tried to see if Jim could make it to the White House in time to come to the Rose Garden to hear the president, but it was just not going to be possible, given the timing.

Everyone realized that this was such a huge moment in history. So many of our colleagues went to the Rose Garden to wait for the president—we could see him in the Oval Office, and he was writing at his desk. Later, we learned that he was making edits to the eulogy that he would be delivering in South Carolina that same day.

Valerie Jarrett: Normally, when there are ceremonies in the Rose Garden, unless you’ve been directly involved in the purpose for the president’s remarks, there’s an unwritten rule: don’t come out and watch. You’re not part of the audience—you’re working in the White House, you should be busy. But that day, the colonnade was jam packed, full of young staff who all wanted to be physically present when the President talked about this incredible case. It was a special moment and gave him a chance to put progress in context, and say, it feels like a thunderbolt, but it’s because of all of the decades of hard work that preceded it. We were so lucky that that thunderbolt happened on our watch.

President Obama [speech excerpt]: Our nation was founded on a bedrock principle that we are all created equal. The project of each generation is to bridge the meaning of those founding words with the realities of changing times—a never-ending quest to ensure those words ring true for every single American.

Progress on this journey often comes in small increments, sometimes two steps forward, one step back, propelled by the persistent effort of dedicated citizens. And then sometimes, there are days like this when that slow, steady effort is rewarded with justice that arrives like a thunderbolt.

Sarada Peri: President Obama wanted to acknowledge how quickly in the span of American history the change had come, but also that change does not feel fast when you are fighting for it, and when your family and your life and your livelihood is on the line.

Valerie Jarrett: I think that was part of his message—these moments don’t happen by accident. They only happen when ordinary citizens roll up their sleeves and really get to work making the case for change.

Sarada Peri: In the speech, we mentioned some of the other victories that had happened over the course of his administration— repealing Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell (Opens in a new tab) ; extending full marital benefits to federal employees and their spouses (Opens in a new tab) ; expanding hospital visitation rights for LGBT patients (Opens in a new tab) . Things that were about the way people go about their lives in an ordinary way. Because I actually think that the ability of people to live their daily lives has ultimately pushed more people to be open to LGBT rights.

Sarada Peri: There was so much energy and adrenaline in the Rose Garden. I was exhausted and had been up early working, so this was sort of a release. And then… I was done. I thought, “Okay, now I’m done with this day, even though it’s only 11:30 in the morning.” We had done the big thing we were supposed to do. But the President’s day was only getting started.

Amazing Grace

Cody Keenan: The morning was full of joy. It was important to all of us who felt that equality matters. And then he had to have to go to a eulogy for something as awful as this, that tore right at our deepest divisions and sins as a country. The Charleston eulogy was for people who were brutally murdered by a white nationalist. There’s nothing joyful about that.

Sarada Peri: He didn’t have to go Charleston—that’s not in the job description of the president—but of course it was a thing that President Obama would do, and really had to do. To speak to the pain of these people who lost loved ones in an act of violent white supremacy—not only speak to their pain, but put that in the broader context of America, and the work we still have to do.

Barack Obama: When Charleston happened, there’s this convergence of a mass shooting and the racial hatred. I remember saying, “Look, I want to go to the funeral and I want to hug the families—I don’t think I want to talk. I don’t know what else to say. I feel as if I have run out of words, because I’ve been doing this so much and it doesn’t seem to have any impact on anything. And I don’t want to perpetuate this notion that somehow this is normal.”

Valerie Jarrett: We had been to so many memorial services by that point for people who had been murdered through gun violence. I had accompanied President Obama when he went to Sandy Hook where 20 children and six adults were murdered. I had accompanied Mrs. Obama back to our hometown of Chicago for Hadiya Pendelton’s funeral, a 15-year-old teenager who was shot just a few weeks after she had marched in the inauguration parade.

He’d spoken about this issue of gun violence and been so determined to get Congress to pass just the most basic legislation to keep guns out of the hands of those who are a threat to themselves or to others in the wake of Sandy Hook. And it was so profoundly disappointing and frustrating that even though the vast majority of the American people supported gun legislation, we couldn’t get Congress to act. And so having given so many eulogies, he said, “What more is there for me to say?”

He asked me to call Mrs. Pinckney to see whether she would prefer that he come as a guest or give the eulogy, and she said, “I really would find it quite comforting if he would give the eulogy.”

Cody Keenan: One of the ways that the president approached a eulogy was, we’re not just here to say nice things about somebody. It’s a missed opportunity when the entire country is your audience. So whenever we did a eulogy, we would include a section that basically addressed, what is our role here? Now that they’re gone, what’s our obligation to carry on now that they can’t do it anymore?

During the previous week, the families of the victims all forgave the killer in open court. And the president seized on it and said, “if I speak in Charleston, this is what it’s going to be.” Over the course of that week, I got him a draft of his remarks. He kept the first half intact and crossed out the second half entirely and reworked it on a legal pad, based on the concept of grace.

Valerie Jarrett: He decided to craft his remarks about the Black church—how our doors are open, even though we’ve had this history of violence and attacks against the church, that the spirit with which a stranger is welcomed, is a part of this culture, part of the religion and faith. It was a way to lift up the life of Reverend Pinckney and the others who had died. But it was also intended to motivate people to say, “We can do better than this.”

Cody Keenan: The President had added the lyrics to “Amazing Grace” to the speech the night before. Just before we got off the helicopter he said, “You know, if it feels right, I might sing it.”

Charles Miller, Jr., Musician, Mother Emanuel AME Church: Many of the other funerals had already taken place leading up to Reverend Clementa Pinckney’s funeral. So, a lot of the members of the church, and the families, were reasonably fatigued mentally and spiritually.

So many dignitaries were in attendance. State representatives and senators were there, as well as our US senators and US representatives. Mayors, police chiefs, the governor. Not to mention local celebrities and national, international celebrities were also there in attendance on that day. And of course, our president, Barack Obama and his wife, Michelle. We knew that they were en-route—we didn’t know when he was coming in and that he was meeting with several of the families before he came into the arena.

Knowing Reverend Pinckney, he was not one for much fanfare, and he wouldn’t have thought that a country boy from a small county in South Carolina would be worthy of all of that attention. But, looking at the accomplishments and the impact that his life had, he was worthy of that and so much more.

Valerie Jarrett: The President and Mrs. Obama met with Mrs. Pinckney and her two adorable daughters right before the ceremony and they were so strong. It helped everybody else steel themselves for this occasion. But when I walked into the venue, which was packed, you could feel the energy and the electricity of a celebration of a life, as opposed to a somber memorial service. It was palpable the second I walked in the room.

Charles Miller, Jr: From the beginning, the service was very spirit-filled. You could really feel the emotion and feel the hearts of each and every individual that was there.

When the choir finished its last selection before President Barack Obama got up, I was playing the organ, accompanying the choir. Usually, I would get off the organ to go sit down somewhere else, but I knew that the choir was going to be singing another selection after President Obama got done, so, those musicians, we just stayed in place.

As President Barack Obama spoke, I listened intently on everything that he was saying, not knowing what was to come.

Barack Obama [speech excerpt]: For too long, we’ve been blind to the way past injustices continue to shape the present. Perhaps we see that now. Perhaps this tragedy causes us to ask some tough questions about how we can permit so many of our children to languish in poverty, or attend dilapidated schools, or grow up without prospects for a job or for a career.

Perhaps it causes us to examine what we’re doing to cause some of our children to hate. Perhaps it softens hearts towards those lost young men, tens and tens of thousands caught up in the criminal justice system and leads us to make sure that that system is not infected with bias; that we embrace changes in how we train and equip our police so that the bonds of trust between law enforcement and the communities they serve make us all safer and more secure.

Maybe we now realize the way racial bias can infect us even when we don’t realize it, so that we’re guarding against not just racial slurs, but we’re also guarding against the subtle impulse to call Johnny back for a job interview but not Jamal. So that we search our hearts when we consider laws to make it harder for some of our fellow citizens to vote. By recognizing our common humanity by treating every child as important, regardless of the color of their skin or the station into which they were born, and to do what’s necessary to make opportunity real for every American—by doing that, we express God’s grace…

It would be a refutation of the forgiveness expressed by those families if we merely slipped into old habits, whereby those who disagree with us are not merely wrong but bad; where we shout instead of listen; where we barricade ourselves behind preconceived notions or well-practiced cynicism…If we can tap that grace, everything can change.

Amazing grace. Amazing grace…

Charles Miller, Jr: As he sang the first word, the first thought in my mind was, Oh wow, he’s really going to sing. So, I’m thinking to myself, Do we play along? I just closed my eyes, said a quick word of prayer, because I knew the world was watching, and let the Lord lead me into what to do next. It seemed like everyone in the arena joined in, and you could really, really, really feel the spirit of the Lord.

Barack Obama [speech excerpt]:

Clementa Pinckney found that grace.

Cynthia Hurd found that grace.

Susie Jackson found that grace.

Ethel Lance found that grace.

DePayne Middleton-Doctor found that grace.

Tywanza Sanders found that grace.

Daniel L. Simmons, Sr. found that grace.

Sharonda Coleman-Singleton found that grace.

Myra Thompson found that grace.

Through the example of their lives, they’ve now passed it on to us. May we find ourselves worthy of that precious and extraordinary gift, as long as our lives endure.

Charles Miller, Jr: When people think of the Emanuel Nine, I hope that they remember each and every one of them as mothers, fathers, cousins, pastors, social change agents, loving Christians as well.

Each and every one of those individuals were loving souls, were persons that not only loved their church, and not only loved the Lord, but they loved their families and they loved their community, and were such integral parts of their community. Folks who didn’t let the color of someone’s skin prevent them from ministering to that person, not even knowing what would be their fate. They just loved everyone, no matter who you were or where you were from.

Valerie Jarrett: When the service ended, President and Mrs. Obama, Vice President Biden and Dr. Biden each went and spent time with the remaining families of the victims who were there. And what struck me about those meetings is every family was trying to figure out what they could do in the name of their loved one to make the world a better place. Each of them felt this sense of responsibility to do something.

Barack Obama: It was their strength, not my strength, that I was relying on. It was their grace that then bathed me in grace.

The Light of Progress

Valerie Jarrett: We left Charleston on an upbeat note. It didn’t feel heavy because of those meetings that we had right after the service. And I think the reaction to “Amazing Grace” was uplifting as well.

But a few weeks earlier, one of my staff, Aditi Hardikar, had come to me with an idea that originated with Jeff Tiller, who worked in the press office.

Aditi Hardikar: In April of 2015, I had one of my weekly check-ins Jeff, who brought up this idea: the Supreme Court’s going to rule on the biggest case in the LGBT community’s history in June. What if we lit the White House in rainbow colors? And importantly, what if we made a commitment to do it regardless of how the Supreme Court ruled?

Later, I met with Valerie and said, “Jeff had this phenomenal idea. It’s probably really hard to pull off. Others might think it’s crazy, but just hear me out. We want to light the White House in rainbow colors on the day that the Supreme Court rules on the Obergefell decision.”

Valerie took a second, and she looked at me and she said, “I think that’s a phenomenal idea. I’m going to talk to Tina Tchen,” who was the first lady’s chief of staff. Tina worked with the residence staff and other partners to actually pull it off.

Jeff Tiller: The idea actually first came about in March 2015. One of the things that drove me personally, that I never really talked about at the time, is that in December 2014, there was a young girl named Leelah Alcorn, and she was transgender. She ended up dying by suicide, sadly. And then days later, there was a “We the People” petition that was posted and submitted online through the White House website that brought attention to Leelah’s suicide and used it to call for President Obama to end the practice of conversion therapy.

It received a lot of signatures very quickly. In April, we released the White House’s response to the petition (Opens in a new tab) and announced that the White House supported efforts to ban conversion therapy nationwide (Opens in a new tab) . We would have to work with cities and states to pass it, because at the time there was no likelihood that a Republican-controlled Congress would pass any type of legislation like that.

Jeff Tiller: Lots of people who work at the White House probably have one or two Americans they were always thinking about on a daily basis. In 2015, every day, Leelah’s story stuck with me. Her story was very familiar. I think a lot of LGBTQ Americans could say, “Her story is not that different than mine.” The lighting of the White House was done for lots and lots of reasons, but being part of the team that made that happen, for me, was partly in response to Leelah.

I was 11-years-old when Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell was enacted (Opens in a new tab) . And as an 11-year-old, I can’t say that I completely knew who I was or had my identity formed, but I think the message I took away from Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell was, remain silent about who you are and your identity or face consequences.

Lighting the White House in rainbow colors doesn’t require any context to understand what the image and message means. At the end of the day, we hoped that someone who was middle aged, or a young kid, who is wrestling with these issues—trying to figure out their identity and who they are—if they came across that image that night, they would understand that the President of the United States supports you. This Administration is fighting for you. Even if that kid is years away from being in an environment that’s supportive, that image could maybe give them some hope that there’s nothing wrong with them. And the people who are in charge support them as human beings and are fighting for them, even though they may not see that every day.

Aditi Hardikar: Apart from marriage equality, there were so many other steps taken (Opens in a new tab) to affirm the dignity and equal protection of LGBTQ Americans since the beginning of the President’s term—he had extended the same protections (Opens in a new tab) that the spouses of straight federal employees would receive to LGBT federal employees, which sent a clear message of how he valued LGBT families and how he viewed those as the same as just any other family. The President signed a presidential memorandum allowing same sex couples to be able to visit their partners in hospitals (Opens in a new tab) , whether it was when they were having a major surgery or potentially on their deathbed. The President provided funding through agencies across the administration to support LGBT homeless youth (Opens in a new tab) , which make up a disproportionate amount of the homeless population in youth in this country due to LGBTQ young people getting kicked out of their family’s homes because they were out, or they were discovered to have been a member of the LGBTQ community. There was a team of lawyers at the Department of Justice and in White House Counsel who had been taking action prior to 2015, like when Eric Holder announced the Department of Justice would no longer defend the Defense of Marriage Act in court. (Opens in a new tab)

We decided to bring all of these people together who had worked in the Administration for the past six and a half years that helped build to this moment to celebrate. Everyone from Pam Karlan, a lawyer at the Department of Justice, to the other two LGBT liaisons that preceded me—Brian Bond and Gautam Raghavan—to people in government agencies. Because often in this work, there are more disappointments than victories. I got permission from the vice president’s staff to use his balcony that overlooks the West Wing and Residence. The majority of the people who had attended had no idea about the plan for the White House to be lit up in rainbow colors.

Valerie Jarrett: We didn’t announce it ahead of time. I put out a tweet that said something like, “Take a look at how the White House will change tonight.”

Aditi Hardikar: We were all in the balcony, again, having a wonderful celebratory moment, and somebody started squinting in the distance, and asking, what’s happening over on the House?

Aditi Hardikar: As the sun went down, the lights got brighter and we all moved to the North Lawn. There were so many tears. People who had gotten married to their same sex partner, people who were in long-term relationships that hadn’t been able to get married, and people who were just openly LGBTQ people that just couldn’t believe their eyes. One lawyer who had worked at the Department of Justice facetimed her partner and asked if she would marry her.

Jeff Tiller: Throughout the night, thousands of people came to Pennsylvania Avenue to take pictures with the White House in the backdrop. To just hang out. The Secret Service said, “Someone has to stay here all night with these lights because if something happens, we don’t know how to turn them off.”

Aditi Hardikar: Outside of the White House on Pennsylvania Avenue, there were throngs of people. There were signs that said, “love is love.” A gay men’s chorus was singing, “America the Beautiful.” I can never talk about it without getting choked up.

Sarada Peri: I get emotional thinking about it now. You could see the magnitude of it on people’s faces. I remember giving Tiller a hug at some point that night and just feeling the emotion of it. I got so many emails and texts from friends—your social media feeds were full of people showing the photo and changing their backgrounds. But I called my best friend and he came down to Pennsylvania Avenue too, and I thought about how far we had come from that night in sophomore year when he quietly came out to me on the futon in my dorm room.

I just didn’t imagine that it could happen as quickly as it did, partly because of my age. I was a teenager when, “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” became policy. As recently as 2008, marriage equality still was not part of the Democratic Party’s platform. It was not just that the legal barriers to equality for LGBTQ Americans seemed so high for so long, but the cultural understanding of equality felt really distant. And of course for the people who struggled for decades, it did not feel fast, but the compression of that progress in the space of about five or six years, required momentum and acceleration.

It was hard to wrap your arms around the magnitude of this for so many reasons, but one of them was because I couldn’t imagine what this would mean for future generations. We had lived in a world where the right to marry who you love was not a reality up until that moment, and now there were going to be people who were born, my children and yours, who would only live in a world where this was possible. That was pretty stunning to think about.

Jim Obergefell: If I think back to when I was a young adult, fully in the closet, 30 years ago, struggling to feel comfortable with myself, I realize back then I had no one to look to as an example. I had no image of leading life or living life as an open gay man who was happy, an open gay man who was truly being themselves.

When I thought of marriage, I always thought, “Well, I’m Catholic. I’m going to marry a woman and have kids,” because that’s what good Catholic boys did. I wish I had had examples of a different way my life could go, and that’s one of the things I love most about our society today.

Recently I spoke at American University, and afterwards, a student came up to me and said, “Jim, I want to tell you something I’ve not told anyone, including myself. I’m like you. I like boys.” To me, those moments when someone feels comfortable enough to share that with me, that means more than anything, because it’s making it clear to me that the world is getting better.

Jeff Tiller: During my time at the White House, I became friends with a gentleman named Gilbert Baker. Gilbert was the creator of the Pride flag. And hearing his stories about his time with Harvey Milk in San Francisco, his stories about making flag after flag, it really helped to give me some perspective that I admittedly did not have.

For decades and decades and decades in this country, people have given their lives in the fight for equality. People have gone to jail—so many sacrifices have been made.

Jim Obergefell: When I think of the people I consider heroes in that fight, the one that pops immediately to mind for me is Edie Windsor—without Edie’s courage in filing her case against the United States, the United States v. Windsor, Obergefell v. Hodges wouldn’t exist. Harvey Milk, someone who gave his life in the fight for LGBTQ equality. Those brave souls at the Stonewall Inn, especially and primarily transgender women of color and people of color—people like Marsha P. Johnson—who said, “This is not right. We are not going to allow this to happen anymore.” If it weren’t for their decision, their righteous anger to push back against what was happening, Pride Month wouldn’t exist.

Jeff Tiller: My partner had come in to see the lighting. We found two lawn chairs and just sat on the North Lawn until 4:30 am staring at the lights.

But before Valerie left, she said, “Did you see the President’s remarks in Charleston?” I said, no, I haven’t looked at any news because of the lighting. And she said, “Before midnight, you need to watch his remarks.”

So before midnight, on my phone, I pulled up Obama’s speech. And I remember bawling my eyes out, watching this on the North Lawn. It really felt like that day encapsulated the range of what you’re dealing with at any given time at the White House.

Sarada Peri: If you could pick one day that explains so much of who we are as a country—good, bad, ugly, all of it, that was the day. It felt like a day that mirrored President Obama’s understanding of the American project—we don’t just make progress; we don’t just take two steps forward and never go back. This struggle is an ongoing one and it zigs and it zags.

In a way, white supremacy has been the biggest blocker of progress on a whole range of issues, including LGBTQ issues. Because it is tied up with the kind of toxic masculinity and exclusiveness that makes it impossible to be anything but what they tell you to be.

I think there are some white people who would like the story of that day to include only the beginning and the end of it, without Charleston in the middle. And, frankly, that is the history we’ve taught—that Rosa Parks was tired, she sat down, and suddenly the Voting Rights Act was passed. There is no reckoning with the ugly and the painful, because that would mean we’d have to look within ourselves.

People fear that acknowledging the unjust, bloody parts of our history means you hate America. That’s the opposite of how President Obama sees America. He believes that loving your country means acknowledging its imperfections and working to make it better. But that’s not always comfortable. And the comfortable view of history was challenged on a day that was already pregnant with meaning, because people had to watch the President of the United States acknowledge the ugly. Charleston was a reminder that the struggle for progress is often violent and people lose their lives in the fight for equality.

Cody Keenan: Five years later, what I see in those 10 days is the culmination of a lot of different movements—decades worth of movements. And a vindication of President Obama’s vision of change.

The civil rights struggle has been going on for 60, 150, 400 years, depending on how you start counting it, and there’s still a long way to go.

The struggle for universal healthcare has been going on for over 100 years now, and it’s still going. The organized movement to keep our kids safe from guns is relatively new, and it really took off only in the wake of all of these shootings. And an organized movement for LGBT rights is also relatively new—about 50 years.

But all of those movements came to the forefront in that same week. That should give people hope and faith that organizing and change can happen, even if it’s unsatisfying, even if it doesn’t give us everything we want, it is possible.

Every time we reach these milestones, we deserve to celebrate for a day, and then keep fighting until you get all the way.

Jeff Tiller: It was just a small evening celebration, knowing that the very next day, we still have to continue working on transgender and gender identity issues. And the work, the fight, never stops. And it never will.