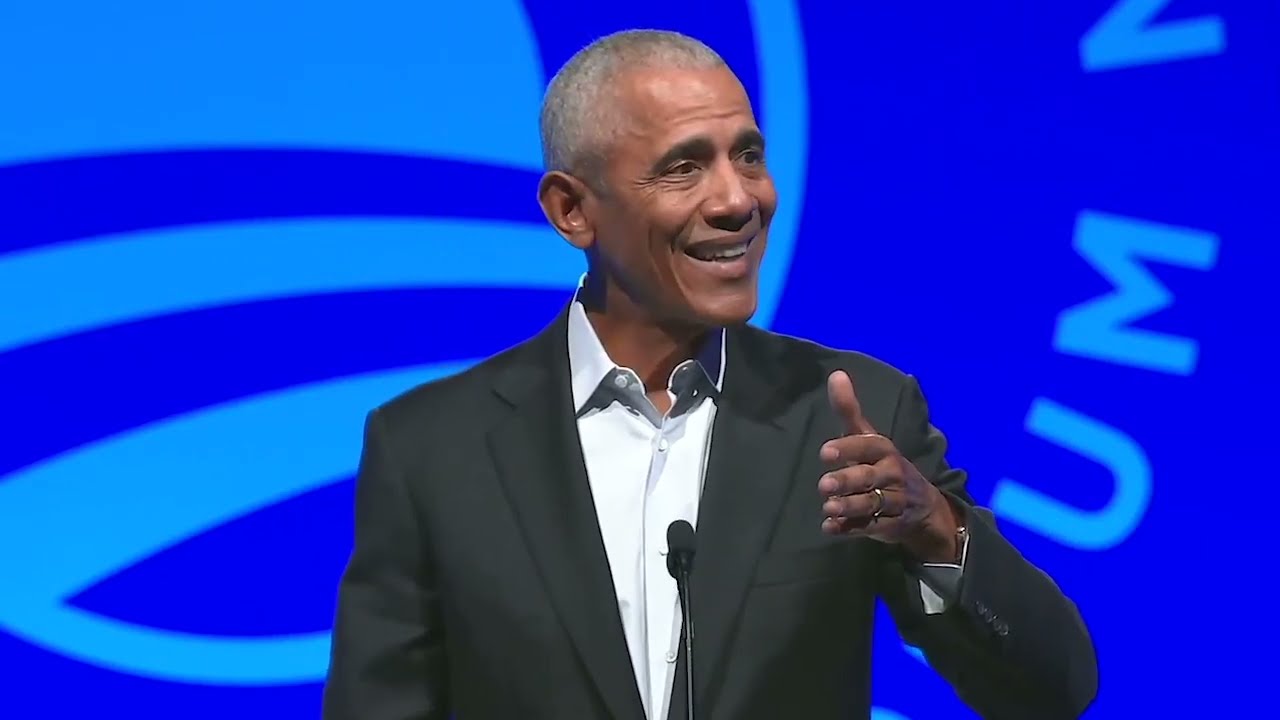

President Obama’s remarks from the 2024 Democracy Forum

Hello, everybody! Hello, everybody! Have a seat! Thank you!

Have a seat! We're going to try to keep this on time! (Laughter). You know, it is good to see all of you. Thank you, Berto, for the introduction. I am very proud of that young man. Thank you for everything that you're doing, Berto, for bringing people here on the south side of Chicago together. I want to thank all of our panelists, the amazing leaders from our network, the outside experts and thinkers and practitioners who took time out of their busy schedules to be part of our third annual Democracy Forum.

Now, I should tell you that when I've mentioned to a few friends that our foundation would be hosting a forum on democracy and pluralism, I got more than a few groans and eye-rolls. And it’s understandable, after all; here in the United States we have just been through a fierce, hard-fought election, and it's fair to say it did not turn out as they hoped. And for them, talk of bridging our differences when the country and the world seem so bitterly divided felt like an academic exercise. It felt far-fetched, even naïve, especially since, as far as they were concerned, the election proved that democracy is pretty far down on people's priority list. I understood their skepticism; maybe you have had a conversation with a friend that felt the same way. But as a citizen and part of a foundation that deeply believes in the promise of democracy—not only to recognize the dignity and worth of every individual, but to produce freer, fairer, and more just societies—I can't think of a better time to talk about it.

You see, it's easy to give democracy lip service when it delivers the outcomes we want. It's when we don't get what we want that our commitment to democracy is tested. And at this moment in history—when core democratic principles seem to be continuously under attack, when too many people around the world have become cynical and disengaged—now is precisely the time to ask ourselves tough questions about how we can build our democracies and make them work in meaningful and practical ways for ordinary people.

And that's why we're here. That's what these forums have been about. Two years ago, we kicked things off by examining the ways that we might counteract the flood of misinformation across the media landscape. Last year, we looked at how disruptions in the global economy and resulting rampant inequality are undermining faith in the democratic process, and we discussed how innovative economic reforms might give more people a stake in the system. So today, we're focused on a third factor that healthy democracies depend on: an idea that political scientists often refer to as pluralism.

Now, let's face it: pluralism is not a word that most of us use in everyday speech. I talked to one young leader earlier this year, who's doing incredible work reducing gun violence here in the United States, and she admitted that she had to look the word up right before our call. But the concept of pluralism should, and is actually familiar to all of us. It means that in a democracy, we all have to find a way to live alongside individuals and groups who are different than us. So we commit to a system of rules and habits that help us peacefully resolve our disputes; we try to cultivate habits—those practices that encourage us not just to tolerate each other but also—every so often—join together in collective action. The pluralist ideal is what allows a Christian church and Muslim mosque to sit side by side on the same city block—and then maybe agree to share a parking lot. It's what keeps you from pulling down a sign in your neighbor's yard supporting a cause you find completely irritating, and it keeps him from doing the same to you; it's what encourages you to team up with a co-worker on a project and get the job done despite the fact that the two of you disagree on abortion, gun ownership, and the merits of Taylor Swift versus Beyoncé.

So this idea, that each of us has to show a level of forbearance towards those who don't look or think or pray like us, that’s at the heart of democracy. And that's hard. Even in relatively homogeneous countries, it’s hard. It's not easy to maintain. Look what happened just this week in South Korea. But it's especially hard in big, multi-racial, multi-ethnic, and multi-religious countries like the United States.

In fact, one way to think about the U.S. Constitution is as a rulebook for practicing pluralism. So you get a Bill of Rights that allows us to think, and speak, and worship, and assemble, and vote on an equal basis, free from government coercion. And with that freedom, we can voice our beliefs and try to persuade others and form coalitions, compete for support, and elect representatives who will then go and negotiate and compromise and hopefully advance our interests.

A majority rule determines who wins and who loses, but the separation of powers and an independent judiciary ensure that the winners don't overreach to try to permanently entrench themselves or violate minority rights.

And just like in a basketball game or tennis match, we agree in advance that so long as the rules of the game are followed, the losers will accept the outcome of any given result, even if they still don't like the other side. Knowing that they'll have another turn to try and come out on top the next time. So that's the theory.

That's how pluralist democracy is supposed to work. It's the story that kids like me who grew up in the Sixties and Seventies were taught in school; what politicians and journalists wax nostalgically about when they talk about the good old days when both society and political parties were more genteel and less vicious and America came together to promote the common good. Of course, in America at least, the reality never fully matched the ideal.

It is true that in the decades right after World War II, our democracy seemed to run relatively smoothly, with frequent cooperation across party lines and what felt like a broad consensus about how interests were shared and differences should be settled, and part of this was the result of America's unique dominance economically in the aftermath of the Great War. So you have industrial competitors all across Europe and Asia who are still digging themselves out of the rubble at the time. That metropolitan that fat corporate profits and rising living standards in the United States helped smooth over friction between competing groups, between management and labor or the industrial and agricultural sectors. Meanwhile, the Cold War generated solidarity against an external threat and a shared perspective on the world that’s constantly reinforced by a handful of TV networks, movie studios, newspaper chains, and magazines that served as nearly everyone's main source of news and entertainment.

Everybody watched Gilligan's Island even if they didn't admit it! See, I know what generation you're from! (Laughter).

But the biggest reason that American pluralism seemed to be working so well mainly had to do with who it left out. The fact is, for most of our history, our democracy was built on top of a deeply entrenched caste system—formal and informal, based on race and gender and class and sexual orientation. A system that excluded or severely limited big chunks of the population from the corridors of power.

Just to give you some perspective: as late as 2005, when I was sworn in as Illinois' junior senator, I was the only African American in the United States’ Senate, 1 out of 100. Only the third since Reconstruction. Out of 100 Senators, there were exactly two Latinos and only fourteen women. It's fair to say that when everyone in Washington looked the same and shared the same experiences and were in the men's side of the Senate gym, because the kind of just women had a closet that they had modified, cutting deals and getting along was a whole lot simpler.

And then starting with the Civil Rights movement in the early sixties, things got more complicated. So in rapid succession, historically marginalized groups—Blacks, Latinos, Asians, Native Americans; women and gays and lesbians; and disabled Americans—demanded a seat at the table. Not only did they insist on a fair share of government-directed resources, but they brought with them new issues, born of their unique experiences that could not just be resolved by just giving them a bigger slice of the pie. So racial minorities insisted that the government intervene more deeply in the private sector and civil society to root out long-standing, systemic discrimination.

Women, the gall of them, called for greater autonomy over their own bodies. While gays and lesbians stepped out of the shadows to demand equal treatment under the law, posing direct challenges to widely held religious and social norms. In other words, politics wasn't just a fight about tax rates or roads anymore. It was about more fundamental issues that went to the core of our being and how we expected society to structure itself. Issues of identity and status and gender. Issues of family, values, and faith. Historically disadvantaged groups began to question the legitimacy of a system as a whole when they had played no part in writing its rules. Public arguments became louder, more contentious, and more emotional. And in the face of all these challenges to the status quo, a lot of people—yes, those at the top of the pecking order, but also those who'd been raised to put their faith in authority and tradition—began to feel that their way of life, the American way of life, was under attack. This would have been a lot for any democracy to manage, even in good times. But of course, all of this was happening against the backdrop of a rapidly changing economy. Changes that would massively increase inequality and widen the divide between rural and urban economies and advantage so-called knowledge workers over those without college degrees. And for a lot of Americans, such changes translated into stagnant wages and rising costs, and it increased their sense that others were benefiting at their expense. And that's not all.

The new economy also upended residential and living patterns, so it reduced the likelihood that people from different backgrounds interacted at neighborhood stores or Little League games. People who were wealthier suddenly sent their kids to private schools. So not only are their kids not interacting with regular folks, but they weren’t either. It contributed to the weakening of, again, political science terms, what folks call mediating institutions: unions, churches, civic organizations—these institutions that had once been the building blocks of democratic participation and a vital bridge between otherwise disparate groups. More and more people found themselves isolated, without natural communities.

And with the Cold War over, with generations scarred by Vietnam and Iraq and a media landscape that would shatter into a million disparate voices, appeals to a common national story or a common national purpose increasingly fell on deaf ears.

And we know what happened next—because we are still living in it. It’s been called the Great Political Sorting that started with the mass exodus of Southern white voters from the Democratic to Republican parties. It is almost now complete, with each party more and more uniform in its beliefs and less tolerant of dissenting views. Media companies have figured out that there's profit in playing to the extremes. Since that's what gets attention, politicians, party leaders, and interest groups are incentivized to take a maximalist position on almost every issue. Every election becomes an act of mortal combat in which political opponents are enemies to be vanquished and compromise is viewed as betrayal, and total victory is the only acceptable outcome. But since total victory isn't possible in a country politically split down the middle, the result is a doom loop of government gridlock, even greater polarization, wilder rhetoric, and a deepening conviction among partisans that the other side is breaking the rules and has rigged the game to tip it in their favor.

Sheesh! No wonder my friends groaned when I told them what I'd be talking about. Now, before I go on, let me acknowledge that I've been focused on the United States since that's what I'm most familiar with. But it's important to point out that the particular struggles of every democracy differ depending on their cultural and political histories. The fault lines of division may be regional and linguistic, like they are in Spain; or religious, as they are in India and Northern Ireland; or ethnic, as they are in my father's homeland of Kenya.

But no matter what country we're talking about, the same basic question remains: Can the idea of pluralism work in the current moment? And, for that matter, is the concept even worth saving? I believe the answer is yes. I am convinced that if we want democracy, as we understand it, to survive, then we're all going to have to work towards a renewed commitment to pluralist principles. Because the alternative is what we've seen here in the United States and in many democracies around the globe. Not just more gridlock and just public cynicism, but an increasing willingness on the part of politicians and their followers to violate democratic norms, to do anything they can to get their way, to use the power of the state to target critics and journalists and political rivals, and to even resort to violence in order to gain and hold on to power. We have seen that movie a lot. So how do we choose the better path? I'm not going to pretend that there are easy answers. Some of the trends I described played out over decades; reversing them is going to take time as well. But as you've heard from many of our panelists

Today, we are seeing successful efforts around this country and around the world to reinvigorate pluralist values. And rather than just repeat what you've already heard from some of our panelists, I'm just going to quickly summarize a few quick principles for us to consider in our work:

Point Number One: Building bridges is not contrary to equality and social justice in fact, it is our best tool for delivering lasting change. Now today, there is a perception, among some advocates, that being adversarial is the main way to make change. Compromise and civility only serve to entrench existing power structures.

And partly this reflects legitimate frustration over the seeming inability of the existing political process to get anything done. And they are certainly right that those in power have often cloaked their resistance to meaningful change by appealing to civil dialogue and lengthy deliberation, and ‘let's form a committee.’ In his Letter From A Birmingham Jail, Dr. King scolded those who counseled patience and seemed more worried about social disruption than rank and justice, saying, "There comes a time,” Dr. King said, “When the cup of endurance runs over and men are no longer willing to be plunged into the abyss of despair." But, Dr. King, like Gandhi, like Nelson Mandela, also understood if you want to create lasting change, you have to find ways to practice addition rather than subtraction.

So let me make this key point: Pluralism is not about holding hands and singing "Kumbaya." It is not about abandoning your convictions and folding when things get tough. It is about recognizing that in a democracy, power comes from forging alliances, and building coalitions, and making room in those coalitions not only for the woke but also for the waking. Now, there are risks involved in engaging with groups you disagree with, particularly if there's a power imbalance involved. There is a risk when you begin to negotiate comprises that you’ll give away too much, that you’ll whittle away your issues to the point where it’s hard to claim that you're making progress. And building bridges may require you to deal with people who not only disagree with you, but do not respect you.

When I was president, there were times, many times, where I was negotiating with people who made it pretty clear they didn't think I should be president, legally, morally. But as long as we're clear about our core principles, as long as we know what our North Star is, we have to be open to other people's experiences and believe that, by listening to these people and building relationships and understanding what their fears are, we might actually bring some of them, not all of them, but some of them along with us. And this isn't just the job of leaders, this is an important point. Advocates and rank and file, in any group, have to be down for compromise as well. Now a few months ago, I talked with a young advocate who said a lot of her work is online, she gets rewarded for taking maximalist positions and she gets punished sometimes if she suggests strategic compromise. And so her incentives led her often to say things that didn't necessarily jibe with how she was feeling, because she was constantly worried, looking over her shoulder, if she gave ground, in order to get three quarters or half a loaf instead of nothing, she might be accused of selling out, which led to fewer followers, and fewer donations and ultimately less influence. In a democracy, it's important to argue strongly for the issues we care about, and draw lines that we're not willing to cross. But purity tests are not a recipe for long-term success.

Point Number Two: Pluralism does not require us to deny our unique identities or experiences, but it does require that we try to understand the identities and experiences of others and to look for common ground. Let me make a note here: A lot of what's labeled identity politics is just folks trying to find an excuse to be able to continue to do what they’ve been doing, in terms of feeling free to call people names or diminish them in some fashion. We understand that. And it's understandable that people who have been oppressed or marginalized want to tell their stories and give voice fully to their experiences - to not have to hold back and censor themselves, especially because so many of them have been silenced in the past. But too often, focusing on our differences leads to this notion of fixed victims and fixed villains.

It creates a presumption that our identities are all singular and static - because you're a male you automatically have certain attitudes and let’s face it, you’re a part of the patriarchy. I have two daughters and a wife and sometimes I'm sitting at the dinner table, like ‘What, what did I do?’

They pick on me, all the time! You know that Broderick! I'm the brunt of every joke, I'm like a sitcom dad.

Or if you're not black, you don't understand, you don't have standing to talk about race. My status trumps yours. Framing issues that way may keep things simple. It's easy to tweet.

Is it still tweeting? Okay. Xing, I don't know.

It may feel satisfying in the short term. Unfortunately, it actually reinforces the sense that we are inevitably, immutably divided and that makes it harder for people to reimagine how they might see themselves and they might see others. In order to build lasting majorities that support justice – not just for feeling good, not just for getting along, to deliver the goods – we have to be open to framing our issues, our causes, what we believe in in terms of "we" and not just "us" and "them."

We have to try to frame issues in ways that at least consider the possibility of a win/win situation, rather than a zero-sum situation. That’s what Mandela understood when he befriends the men guarding his prison cell. That's what King understood in framing the issue, not simply as an African American issue, but as an American issue. Who are we? What are we trying to be? Understanding that the oppressor is as yoked and confined and limited by these systems as the oppressed. And we have to acknowledge that we all have multiple identities. I'm a 63-year-old African American man, for example, but I'm also a husband, I am a father, and a Christian who is constantly wrestling with doubts about organized religion. I am a writer, I'm a Bears fan, which has not been easy! Recognizing and listening for those multiple identities as opposed to just looking at somebody and saying, ‘oh they're that kind of way,’ being open to the fact that even the folks we disagree with most might have something that surprises us, that's an opportunity that we cannot afford to miss.

Third Point: Pluralism works better when it is about action and not just words. Some of you probably remember this right after George Floyd was killed, you got all of these corporations that were putting up ads, and hosting convenings and then they’re instituting mandatory seminars for the workers, where everybody has to get together and talk about how they're probably racist, and how deep the problem runs in our society.

I wrote down this speech, while their intentions are good – but I'm not sure I believe that --there is a little bit like let's get over on the cheap, but let’s assume sometimes the intentions were good. Nothing changed. And unsurprisingly, four years later, all those seminars disappeared. Words alone do not build trust. Words alone do not rid people of prejudice. What does build trust, because it builds relationships, is people banding together to get stuff done. Whether it's a mosque and a synagogue joining forces to help victims of a natural disaster, or a Black community linking up with a traditionally hostile white community in Chicago to try and stop a highway from running through both neighborhoods. Such common efforts take time. They require an investment on the part of the participants.

It won't eradicate people's prejudices, but it will remind people that they don't have to agree on everything to at least agree on some things. And that there are some things we cannot do alone.

Which leads to my final point: We are not born with the muscles to make pluralism a habit, it takes practice, and we need to rebuild the institutions that can give us that practice. A part of that would ideally mean making government work better. I believe, for example, that if we establish non-partisan redistricting here in the United States, it would allow more candidates to compete for every vote as opposed to just appealing to the most partisan members of their base. But let's face it, in our current polarized environment, political reforms are probably not going to happen anytime soon, at least not the ones I want to see.

Which is why this may need to start by just looking for opportunities for people to once again become a part of a society of joiners. Create more organizations from elementary school all the way through adulthood, that bring people together to do something. I’ll give you an example: at a time when organized religion all over America is struggling and in some denominations collapsing, mega churches are actually growing in leaps and bounds. In some cases, really quickly. And while I’m sure there are many reasons for this, one of the reasons is that mega churches understand that belonging precedes belief. If you show up at one of these churches, they don't start off peppering you with questions about whether you've accepted Jesus Christ as your Lord and Savior. They don’t quiz you on the Bible. They invite you in, introduce you around, give you something to eat, tell you all about the activities and groups you can be a part of from the young adult social club to the ballroom dance group to the men's choir which for those of you not familiar that's where they put folks whose voices aren't quite good enough to be in the main choir. But who are allowed to perform maybe once every fourth Sunday. The point is,

megachurches -- I'm sorry, brother? Are you in -- you know what I'm saying is true. (Laughter).

The point is megachurches are built around ‘let's get you if here, doing stuff, meeting

people, and showing you how you can participate and be active.’ It is about agency and relationships, it is not about theology or handouts. And they’re trying to create a big tent where lots of different people can feel comfortable. Once that happens, then they can have a deeper conversation about faith in a way that folks aren't spooked by. What megachurches are doing is also a good argument for localism. Lots of us obsess about our press, social media, obsesses with what's happening in Washington and I understand that because it can be crazy.

A lot of our best work will happen from the bottom up instead of the top-down. If

we're going to get better at pluralism, it's going to happen in the neighborhoods, in the communities where we spend our time, and in the schools where our kids

develop the skills and learn how to negotiate and work together across differences. Now, at

this point you may be thinking, "All that sounds pretty good, but pluralism depends on

everyone following a certain set of rules, that's what you say, Obama.

What happens when the other side has repeatedly and abundantly made clear they're not interested in playing by the rules?”

It's a problem. And when that happens, we fight for what we believe in. There are going to be times, potentially, when one side tries to stack the deck and lock in a permanent grip on power, either by actively suppressing votes, or politicizing the armed forces, or using the judiciary or criminal justice system to go after their opponents. And in those circumstances, pluralism does not call for us to just stand back and say ‘well, I’m not sure, that’s okay’. In those circumstances, a line has been crossed and we have to stand firm and speak out and organize and mobilize as forcefully as we can.

But, even in those circumstances, it's important to look for allies in unlikely places. And too often, we assume that people on the other side have monolithic views when, in reality, some of

them may share our beliefs in sticking to the rules, observing norms, and that's why, when it is appropriate, there is nothing wrong with reinforcing and lifting up elected officials or voters, your neighbors, your friends, who you may not disagree with anything but they do agree with you on that. Because they may be able to exert influence on people they’ve got relationships with within the other party. So, none of this will be easy. Building up these habits and practices that so often we’ve lost. Learning to trust each other again, that's a generational project.

Which is why I'm so excited about the young people, some of whom you’ve already heard from today and who you will hear from in a moment, who are experimenting with different ways to do this. I'm thinking about leaders like Lumir Lapray, a community organizer in France who is training a network of rural changemakers in a country where extremism dominates many villages. Or Ayu Kartika Dewi, who started a program in Indonesia that sends children and their mentors to different parts of the country during school holidays to live with a family from a different cultural background. Leaders like Lumir and Ayu are showing us the way. And what they're discovering is that, when they apply the principles we just talked about - when they listen, they recognize their multiple identities, seek out common experiences and common values - they're not just strengthening democratic habits. They're building stronger organizations, which means they can deliver better results, concrete results for their members.

That is the power of pluralism. That's how we break this cycle of cynicism that's so prevalent in our politics right now, and ultimately, that’s how we’re going to solve some of the greatest challenges of our time.